You can have any colour, as long as it's black

By

Tony Self

An allegory is a means of representing an idea using symbolic

representation. It is a kind of extended metaphor. It occurs to me that motor

vehicle manufacturing can be used as an allegory for the business of technical

communication. Let me explain... from the beginning.

The motor car was invented in Europe (Germany, to be specific), and at

the start of the 20th Century, most motor vehicles were made in Europe. We may

think of the United States as the home of the motor car, but in 1902, a total

of 314 cars was produced in America. By contrast, the most prolific motor

manufacturing country, France, produced 23,000 cars in that same year. Belgium

was producing far more cars than the US. But just four years later, in 1906,

the USA overtook all other car manufacturing nations when it produced 58,000

cars. So how did the US transform from a car manufacturing backwater to a

powerhouse? One reason was that America was a wealthy country, and at the start

of the 20th century, only rich people could afford cars. Although America had

lots of rich people, for motor vehicle manufacturing to be a big industry, it

needed to develop a mass market.

The man credited with working out how to create a mass market for cars

was Henry Ford. He started with the premise that for more people to be able to

afford cars, cars needed to be cheaper. This idea sounds simple enough, but in

reality, it meant bringing the cost of a car down from around $4000 (twice the

average annual income) to less than $1000. Different manufacturing ideas had

already been introduced, such as outsourcing (the Olds company came up with

this when their factory burned down) and using standardised parts that could be

interchanged among several models (an idea developed by Cadillac). Remember,

this is an allegory, so the words

"outsourcing" and

"interchange" are important to note.

In 1908, Henry Ford introduced the

"assembly line" for motor vehicle construction. The first car

model to be produced on the production line was the Model T. The assembly or

production line replaced the

"coachbuilding" method of building cars (where cars were built

individually, one by one).

The Model T Ford

Ford's assembly line was what we would now call

"transformative process engineering". The assembly line was built on

a foundation of standardisation: standard processes to produce simple

components in a standardised production system. To understand how

standardisation created such an opportunity for efficiency, we need to know the

methods that preceded those of Ford. (The terms

"standard processes",

"simple components", and

"standardised production systems" are key to the allegory.)

Coachbuilding Tradition

Before the assembly line, motor vehicles were made by artisans.

Purchasing a motor vehicle was a two-step process: first you would buy a

chassis (from a

"chassis maker"), and then you would take it to a

"coachbuilder". The chassis maker would supply the chassis,

the drive train (engine, gears, axles and wheels), the suspension, the

radiator, and the steering system. The coachbuilder would build a body for the

chassis to suit the customer's needs. If the customer needed four seats, the

coachbuilder would build a four-seat cabin. If the customer needed a small

truck, the coachbuilder would build a two-seat cabin with a tray on the same

chassis. The chassis maker worked in metal, and the coachbuilder worked in wood

and leather. Sometimes, chassis makers and coachbuilders would team up to offer

a packaged product. For example, Fisher Body teamed up with Cadillac to build

all the closed-body Cadillacs of the 1910s.

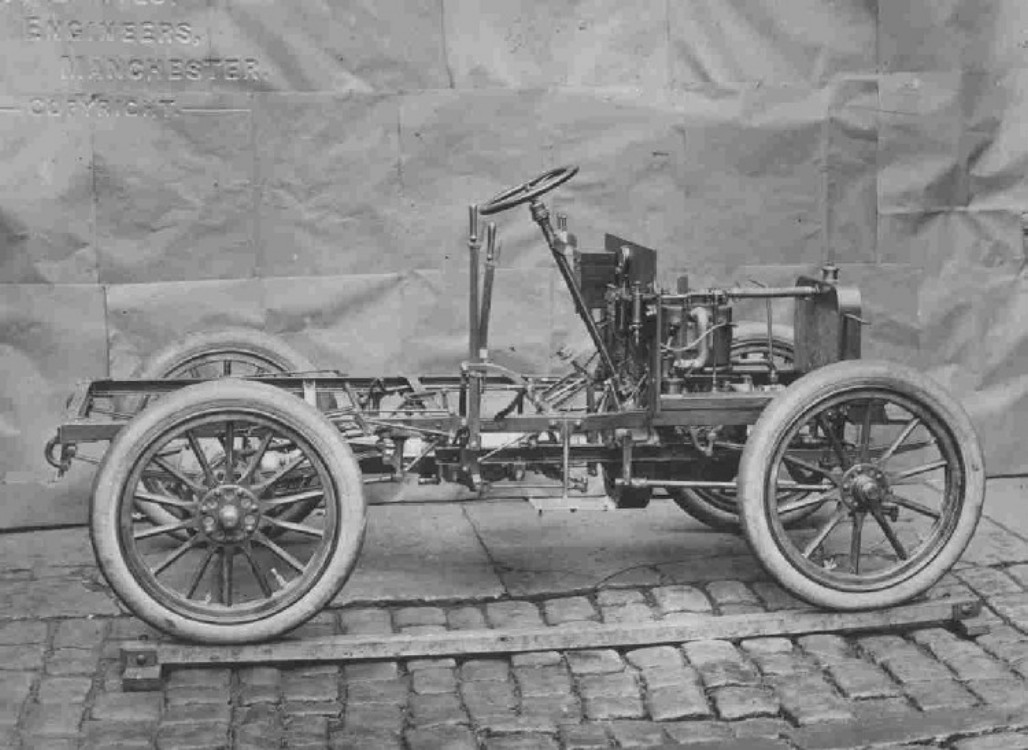

The Chassis Maker's Product - Royce 15196

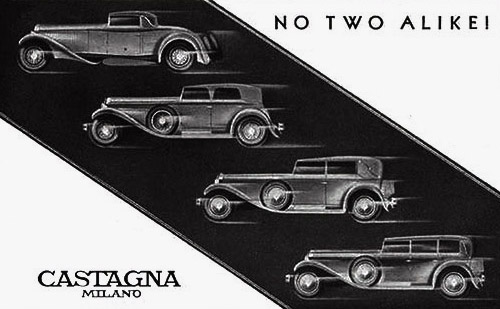

The Coachbuilder's Boast - No Two Alike

Even after Henry Ford's assembly line had transformed manufacturing

and half of all cars in America were Model Ts, coachbuilding persisted.

In sharp contrast to Ford, Rolls-Royce was very slow to embrace the

assembly line. Up until World War II, every Rolls-Royce was produced by

artisans in the coachbuilding tradition, as a rolling chassis to be later sent

to an independent coachbuilder.

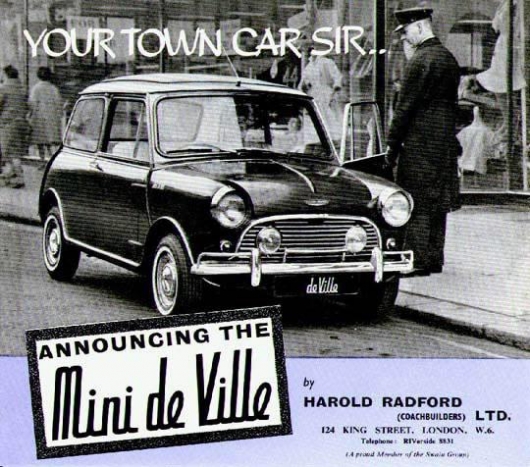

In the 1960s, it became popular for the wealthy to use coachbuilders

as a way of creating exclusive and expensive versions of mass-produced

(assembly line) cars, including the humble Mini. Hooper, the Rolls-Royce

coachbuilders, created the first luxury Mini in 1963 at four times the cost of

a standard Mini. The most famous of the Hooper Minis was one owned by Peter

Sellers; this car featured a hand-stencilled wicker-work effect body

decoration. Radford Coachbuilders produced the Radford Mini de Ville, which was

snapped up by celebrities such as Britt Ekland, all four of the Beatles, Mike

Nesmith (of the Monkees), and Marianne Faithful. A standard Mini Cooper cost

850 pounds; a Radford cost 2,500.

A Coachbuilt Mini for the Wealthy

Even today, over a century after the introduction of Ford's assembly

line, coachbuilders still exist, but they have become niche companies servicing

the wealthy. Car manufacturers with a reliance on coachbuilding are now all but

extinct.

Now remember, this is supposed to be an allegory. How is this history

of car manufacturing symbolic of the business of technical communication? I'll

get to that shortly...

Any colour, so long as it's black

The assembly line is a manufacturing process where parts are added to

a product in a sequential manner using

"division of labour", where one person repeatedly performs

only one small portion of the entire process. Practically speaking, this means

that one person's job might be to hammer the spokes into the wheels; nothing

more, nothing less. The spoke hammerer becomes an expert at spoke hammering,

and becomes more and more efficient at that task. If the spokes and the wheels

arrive at the spoke hammerer's position at exactly the right time, and this is

repeated for all the different tasks in the line, the car can be produced at

the lowest unit cost.

One of Henry Ford's famous quotes about the Model T was, "Any customer

can have a car painted any colour that he wants, so long as it is black."

The Model T only came in black because the production line required

compromise so that efficiency and improved quality could be achieved. Spraying

different colours would have required a break in the production line, meaning

increased costs, more staff, more equipment, a more complicated process, and

the risk of the wrong colour being applied.

The Model T - The Universal Car

Using the car manufacturing metaphor, we can say that technical

communication is still largely in the coachbuilding era, where artisans

hand-craft unique document products using all-in-one tools such as FrameMaker,

Word, RoboHelp, and Flare. Non-standard products with non-interchangeable

components are produced, at a cost that only the wealthy customers and

employers can afford. Technical communication as a profession risks going the

way of coachbuilders... still around, but as an eccentric coterie producing

lovely and obsolete products that very few can afford.

Let's look at the parallels...

Parallels

In the coachbuilding era, a single craftsman or team of craftsmen

would create each part of a product. They would use their skills (developed

over years as an apprentice) and tools to create the individual parts. Those

same craftsmen would then assemble the parts into the final product, making

"trial and error" changes in the parts until they fitted.

This is the same approach that many technical authors currently use to

produce manuals. A single author or team of authors creates each part of a

manual. They use their skills and tools such as word processors and page layout

software to create the individual chapters, pages and images. They then

assemble them into the final manual, making

"trial and error" changes to the layout until the text fits.

Let's analyse this allegory a little further. The assembly line was

made possible by two major technological developments:

- toolpath control (where

jigs and templates provided a means for repeatable, consistent use of tools)

- machine tools (such as

power drills, lathes and milling machines)

These developments not only improved quality, but enabled

"interchangeable parts". In coachbuilding, adjoining parts

were made to fit each other. In assembly lines, different parts needed to be

made in isolation, yet had to fit together when assembled. In document

engineering, the equivalent idea is known as

"interchangeability"; blocks of text from one document need

to be able to work in different documents, and content produced by different

authors and even different companies needs to be able to fit together without

rework.

Interchangeability relies on

"tolerance", and tolerance is defined through standards.

Some people claim that moving away from coachbuilder writing will lead to a

loss of quality. Sure, there are compromises that have to be made (any colour

as long as it's black), but variety may not be quality. Mass production

requires components to be built to higher engineering tolerances than

hand-crafting. For parts to be interchanged, they have to be of consistent

quality, and a quality that is specified. Document engineering, provided it is

working to fine tolerances, produces consistently better quality than

hand-crafting.

Better, Faster, Stronger

Remember Ford's aim of producing a car that costed $1000 instead of

$4000? A Model T cost $825 in 1908, but was $575 by 1912. The price of the

Model T kept dropping as the production line process was improved, and the

skills of workers developed. At the end of the production run, the price was

$300, and a total of 15 million Model Ts had been produced. Even Ford's own

factory workers could afford to buy a Model T. Without undergoing a

revolutionary change in approach, are our document products going to get

cheaper and cheaper? Not if we stick with coachbuilding!

Like toolpath control and machine tools, XML and DITA are catalysts

that can revolutionise technical communication, taking it from coachbuilding to

the assembly line and beyond. (We'll find out what followed the assembly line

later.) XML and DITA: these two

standards allow information

"interchange",

"outsourcing",

"specialisation of labour",

"simple re-usable components", and

"standardised publication systems", but they also demand

skilled technical authors. XML and DITA also make it possible to reduce the

cost of documentation to the same degree that assembly-line reduced the cost of

cars.

DITA projects sometimes fail because authors try to replicate the

coachbuilding approach. They want to keep offering manuals in a colour other

than black. Projects also fail because authors are not skilled in the new

techniques of structured, componentised, topic-centric authoring. Ford faced

the same issue of worker skills.

Ford recognised that the skills of the workers had a direct impact on

quality and efficiency, so opened a worker training college, and paid his

workers a handsome wage of $5 per day. This wage was seen as extraordinarily

high (double the going rate for factory workers), and Ford added money

management courses to the training programme to ensure his employees used their

wages responsibly! And on top of that, he cut one hour off the working day.

Ford's profit doubled in the three years after the introduction of the worker

training college.

Each Ford worker was a specialist, and was recognised as such.

Likewise, DITA authors are specialists: document engineers that need to be

recognised as such.

Beyond the Assembly Line - Automation

Henry Ford's assembly line was embraced by all manufacturing

industries. This resulted in lower costs of mass-produced manufactured goods,

and led, rightly or wrongly, to the

" consumer culture". But progress

didn't stop at the assembly line, and neither does this allegory.

The assembly line method of car manufacture remained the norm until

the 1980s, when many of the production line jobs previously performed by humans

were automated.

"Robots", as they were initially described, took over a lot

of precision, dangerous or repetitive processes. Not only did automation lead

to more consistent components, but worker injuries, including repetitive strain

injuries, were reduced. Today, 50 per cent of all robots are used in car

manufacture. Japanese car manufacturers were the first to take advantage of

robots, and the perception of quality of Japanese cars was reversed. In the

1970s, Japanese cars (

"Jap Crap") were considered of inferior quality to

American or European cars. By the turn of the century, Japanese manufacturer

was synonymous with consistently good quality. While robots replaced humans on

the production line, they also created higher paid, higher skilled and

intellectually stimulating jobs in computer-aided design and manufacture.

Automation in car manufacture

One of the huge benefits of DITA (and other types of XML) is the

opportunity for document automation. In many cases, DITA topics can be

automatically generated. For example, Visma Software developed a little

software utility that generates 13,000 reference topics documenting database

structures automatically, in less than an hour. As in the Japanese car

industry, automation of tedious, repetitive documentation tasks remove drudgery

and leave authors to tackle the more intellectually stimulating tasks.

Automation really means

"the automation of drudgery".

Where now for technical communication?

The catalysts for change are here. As technical communicators, we have

to make decisions on what path we take. We can choose to fight on as

coachbuilders, finding a romantic niche as crafters of expensive, high-end,

bespoke, non-standard documentation products. We can choose to move to the

efficient production line, embracing the division of labour, working to

standards (engineering tolerance), writing for interchangeability, and

transferring as many tasks as possible to automation.

The semi-automated assembly line approach is the one that should be

taken with DITA and XML. If we try to incorporate all the features of the

coachbuilding way of producing documents, we will lose many of the efficiency

and quality control benefits of the new DITA and XML methodology. As well as

vision, investment of time and equipment is required to move from coachbuilding

to assembly line to automation of drudgery, but that investment is worthwhile.

Postscript

Model Ts were originally offered in a blue, red, green and grey. From

1913, black was the only option. More than 30 different types of black paint

were used on different components, and black was the cheapest, most durable,

and easiest to colour-match.

Ford almost went broke when they tried to produce multiple products

with multiple options in the 1930s. Only retained profits from the Model T

saved the company.

It is estimated that as many as 150,000 Model Ts still exist, with

perhaps 20,000 still on the road.

Links